The bang package simulates from the posterior distributions

involved in certain Bayesian models. See the vignette Introducing bang: Bayesian Analysis, No

Gibbs for an introduction. In this vignette we consider the

hierarchical 1-way Analysis of variance (ANOVA) model:

where

,

so that

,

and

and all random variables are independent. Variability of the response

variable

about an overall level

is decomposed into contributions

from an explanatory factor indicating membership of group

and a random error term

.

This model has

parameters:

and

.

Equivalently, we could replace

by

.

The full posterior

can be factorized into products of lower-dimensional densities. See the

Appendix for details. If it is assumed that

and

are independent a priori and a normal prior is set for

then the only challenging part of sampling from

is to simulate from the two-dimensional density

.

Otherwise, we need to simulate from

.

The bang function hanova1 uses the rust

package (Northrop 2017) to simulate from

these densities. In sampling from the marginal posterior density

we use a parameterization designed to improve the efficiency of

sampling. In this case we work with

.

We illustrate the use of hanova1 using two example

datasets. Unless stated otherwise we use the default hyperprior

,

that is, a uniform prior for

for

(see Sections 5.7 and 11.6 of Gelman et al.

(2014)). A user-defined prior can be set using

set_user_prior.

Late 21st Century Global Temperature Projection Data

The data frame temp2 contains indices of global

temperature change from late 20th century (1970-1999) to late 21st

century (2069-2098) based on data produced by the Fifth Coupled Model

Intercomparison Project (CMIP5). The dataset is the union of four

subsets, each based on a different greenhouse gas emissions scenario

called a Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP). Here we analyse

only data for RCP2.6. Of course, inferences about the overall

temperature change parameter

are important, but it is also interesting to compare the magnitudes of

and

.

If, for example, if

is much greater than

then uncertainty about temperature projection associated with choice of

GCM is greater than that associated with the choice of simulation run

from a particular GCM. See Northrop and Chandler

(2014) for more information.

library(bang)

# Extract RCP2.6 data

RCP26_2 <- temp2[temp2$RCP == "rcp26", ]

There are 61 observations in total distributed rather unevenly across

the 38 GCMs. Only 28 of the GCMs have at least one run available for

RCP2.6.

# Number of observations

length(RCP26_2[, "index"])

#> [1] 61

# Numbers of runs for each GCM

table(RCP26_2[, "GCM"])

#>

#> ACCESS1-0 ACCESS1-3 bcc-csm1-1 bcc-csm1-1-m BNU-ESM

#> 0 0 1 1 1

#> CanESM2 CCSM4 CESM1-BGC CESM1-CAM5 CMCC-CM

#> 5 6 0 3 0

#> CMCC-CMS CNRM-CM5 CSIRO-Mk3-6-0 EC-EARTH FGOALS-g2

#> 0 1 10 2 1

#> FIO-ESM GFDL-CM3 GFDL-ESM2G GFDL-ESM2M GISS-E2-H

#> 3 1 1 1 1

#> GISS-E2-H-CC GISS-E2-R GISS-E2-R-CC HadGEM2-AO HadGEM2-CC

#> 0 1 0 1 0

#> HadGEM2-ES inmcm4 IPSL-CM5A-LR IPSL-CM5A-MR IPSL-CM5B-LR

#> 4 0 4 1 0

#> MIROC-ESM MIROC-ESM-CHEM MIROC5 MPI-ESM-LR MPI-ESM-MR

#> 1 1 3 3 1

#> MRI-CGCM3 NorESM1-M NorESM1-ME

#> 1 1 1

# Number of GCMs with at least one run

sum(table(RCP26_2[, "GCM"]) > 0)

#> [1] 28

We use hanova1 to sample from the posterior distribution

of the parameters based on the (default) improper uniform prior for

,

described in Section 11.6 of Gelman et al.

(2014). This prior fits in to the special case considered in the

Appendix, with an infinite prior variance

for

.

# The response is the index, the explanatory factor is the GCM

temp_res <- hanova1(resp = RCP26_2[, "index"], fac = RCP26_2[, "GCM"])

# Plots relating to the posterior sample of the variance parameters

plot(temp_res, params = "ru")

plot(temp_res, ru_scale = TRUE)

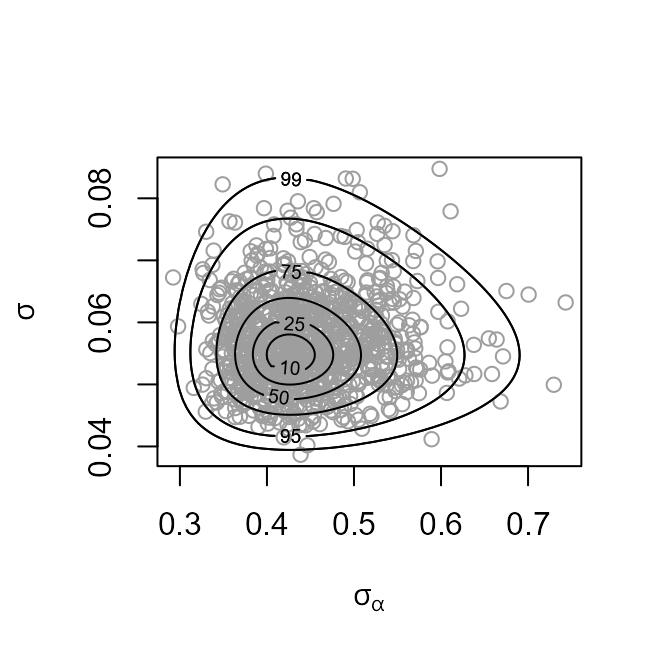

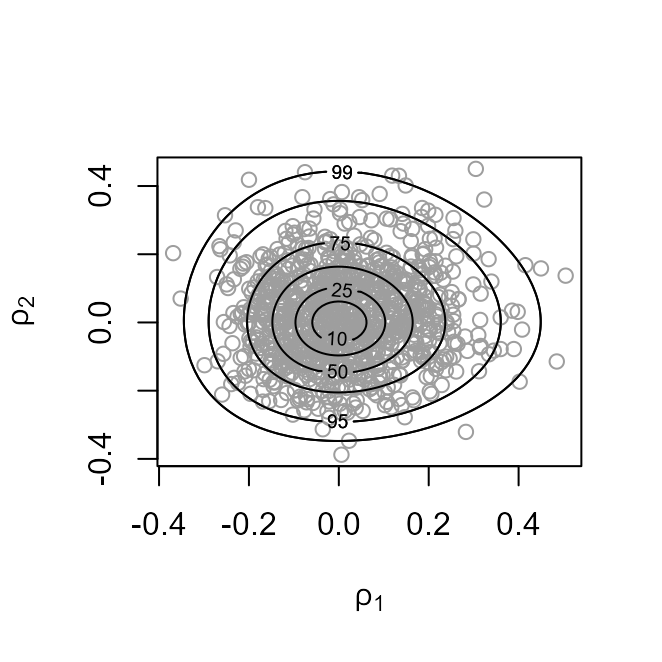

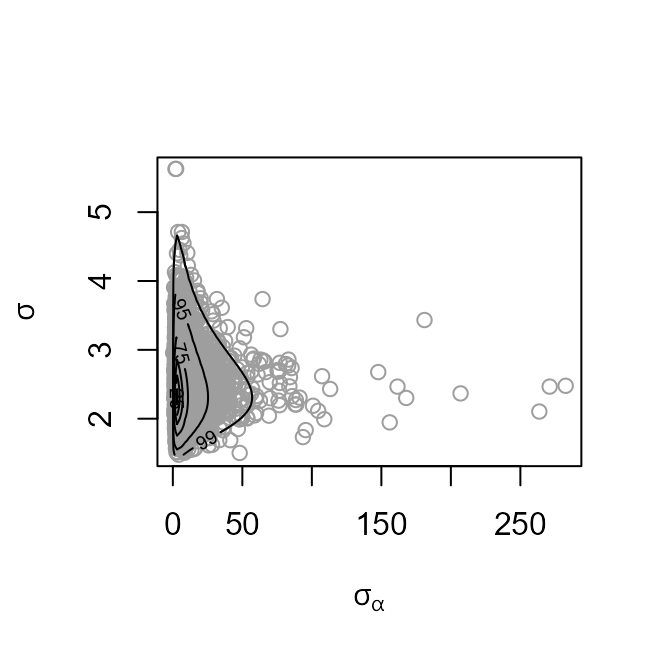

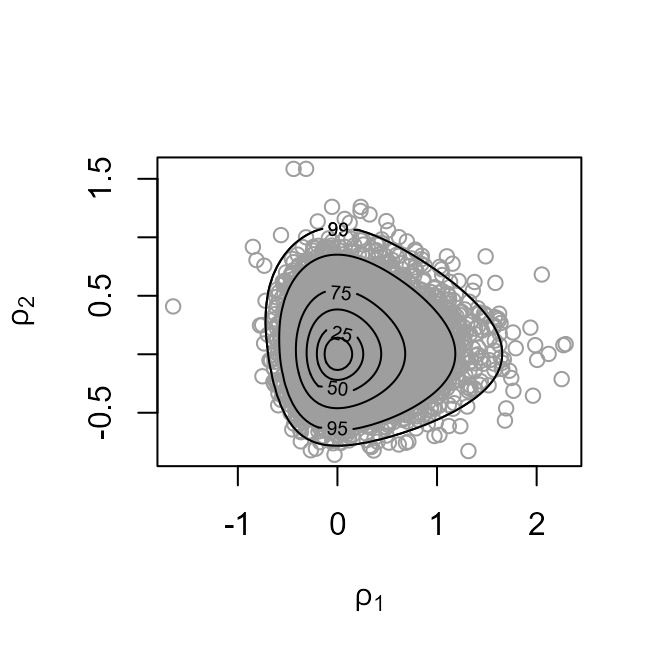

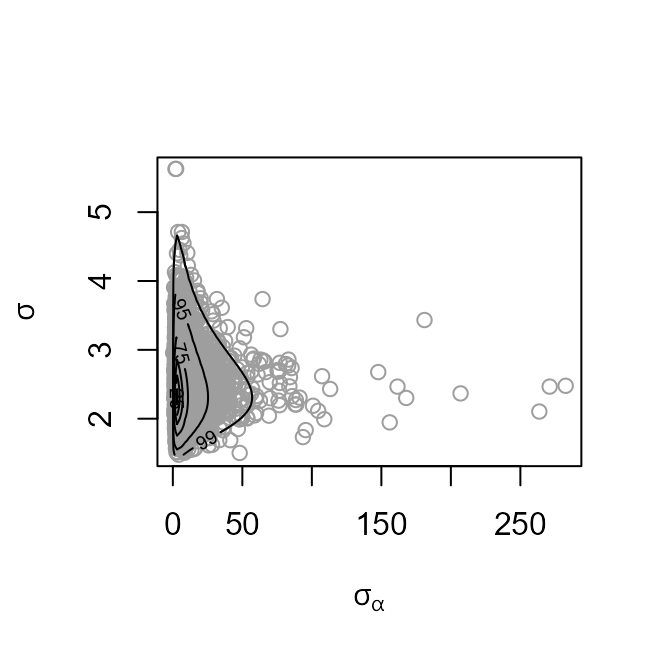

The plot on the left shows the values sampled from the posterior

distribution of

with superimposed density contours. We see that the posterior

distribution is located at values for which

is much greater than

,

by a factor of nearly 10. On the right is a similar plot displayed on

the scale used for sampling,

,

after relocation of the posterior mode to the origin and rotation and

scaling to near circularity of the density contours.

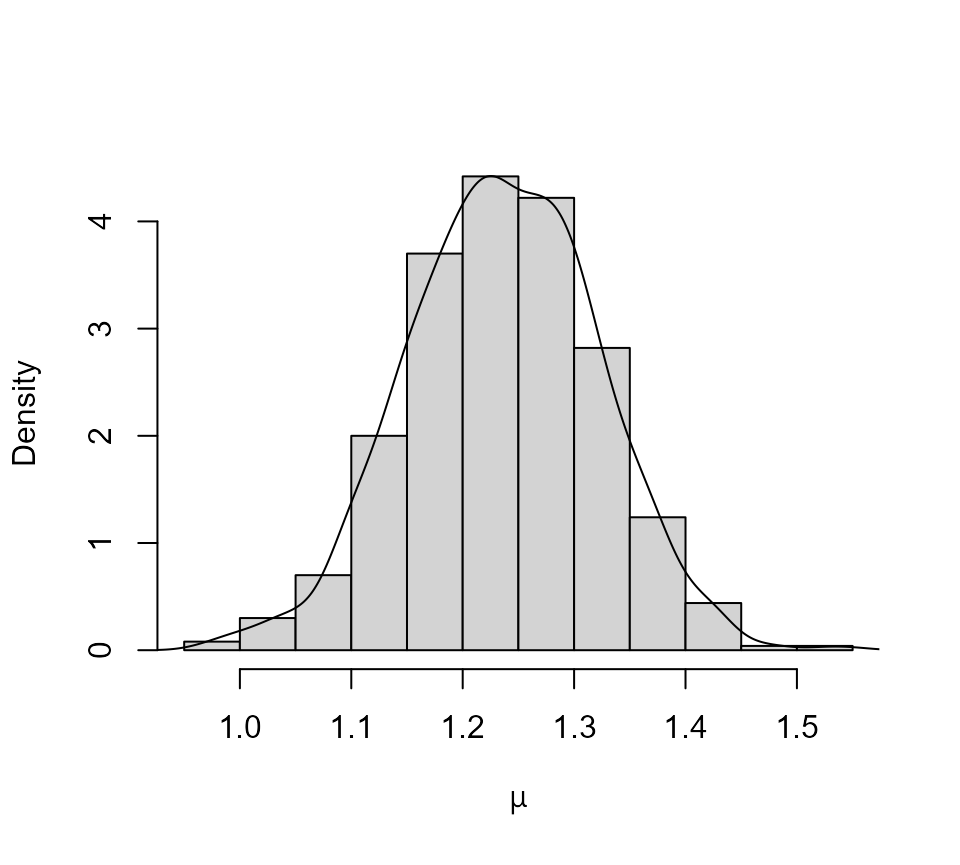

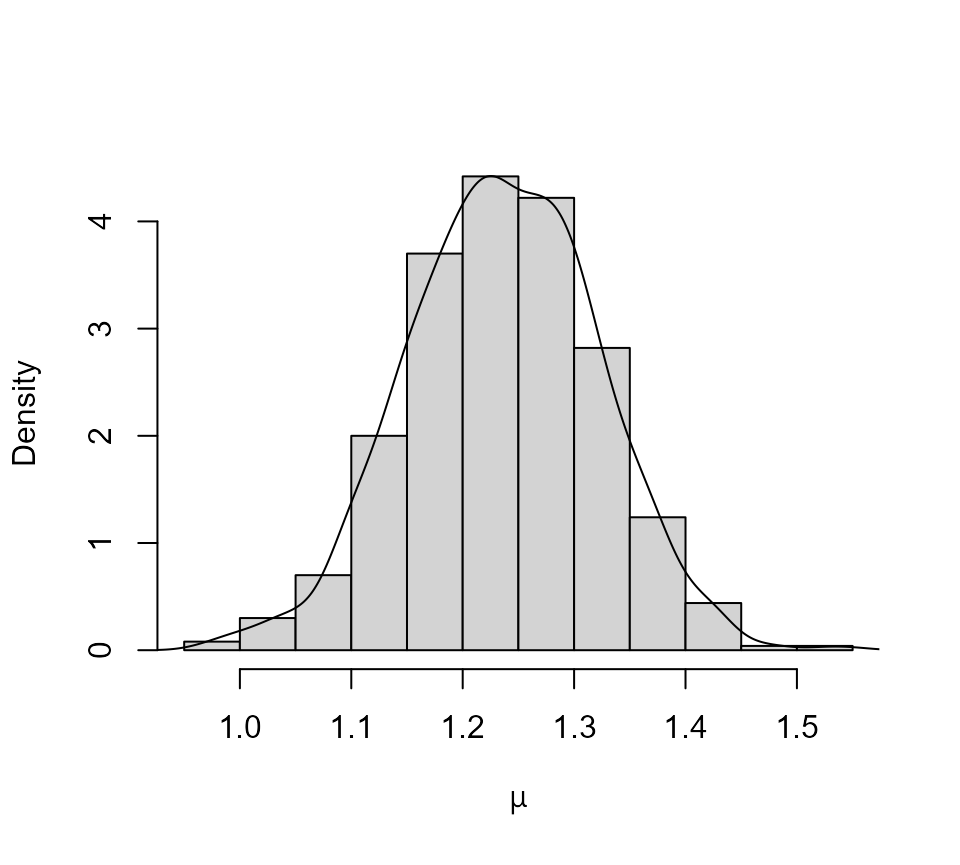

We summarize the marginal posterior distribution of

using a histogram with a superimposed kernel density estimate.

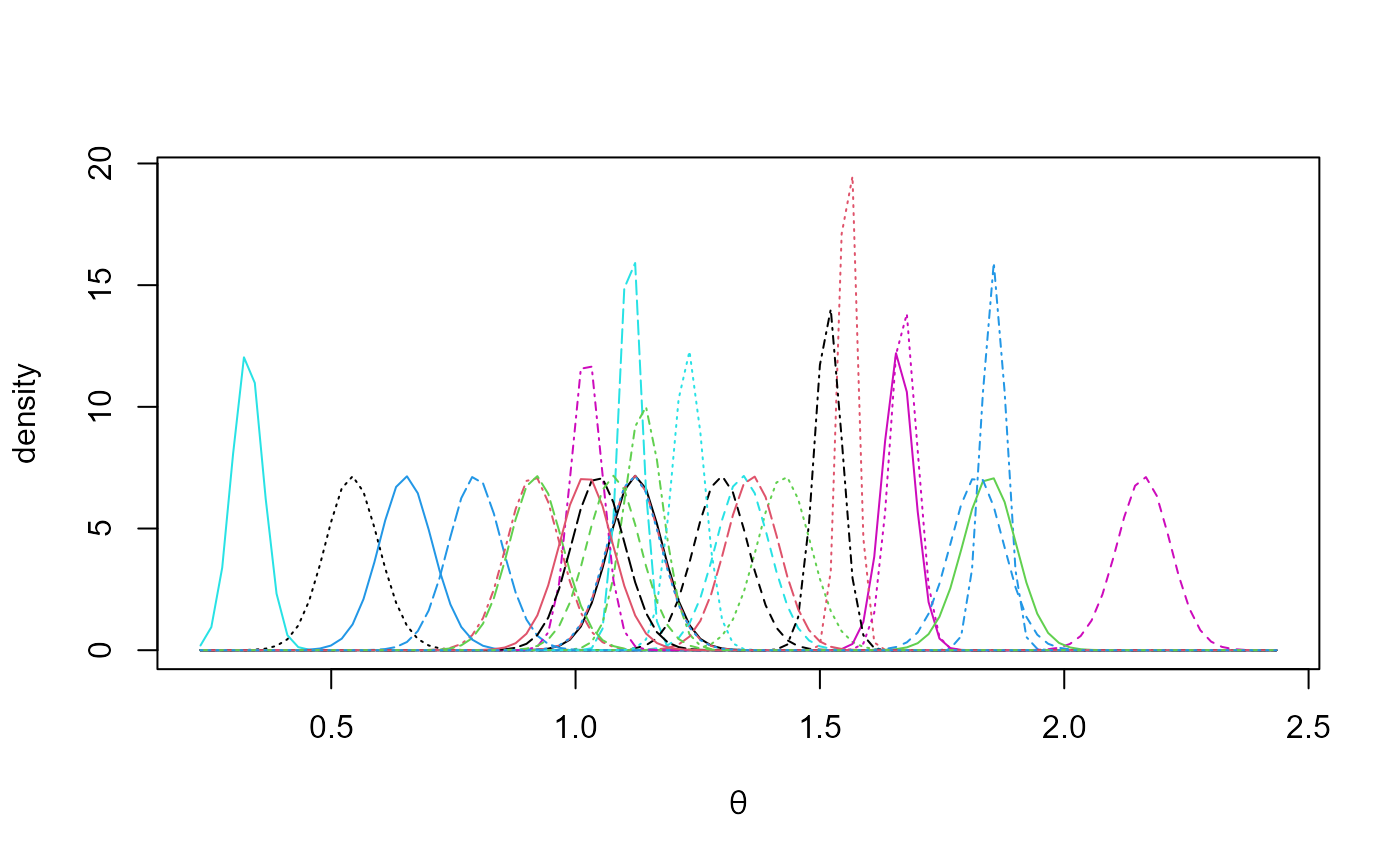

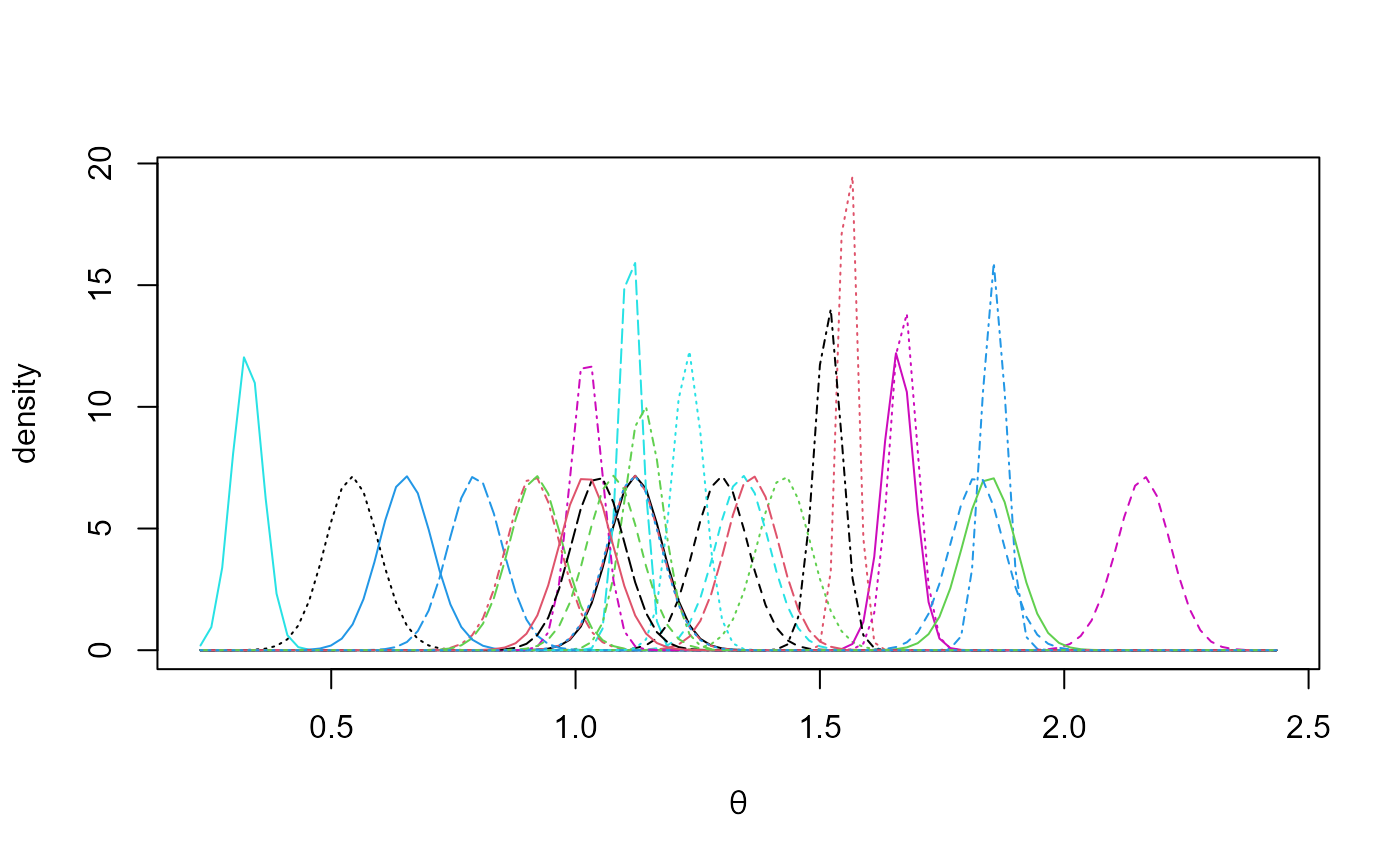

The following plot summarizes the estimated marginal posterior

densities of the mean index for each GCM.

plot(temp_res, params = "pop", which_pop = "all", one_plot = TRUE)

Coagulation time data

In the temperature projection example sampling was conducted on the

scale

and was unproblematic. It would also have been unproblematic had we

sampled on the original

scale. To show that there are examples where the latter is not the case

we consider a small dataset presented in Section 11.6 of Gelman et al. (2014). The response variable is

the coagulation time of blood drawn from 24 animals allocated to

different diets. The crucial aspect of this dataset is that the

explanatory factor (diet) has only 4 levels. This means that there is

little information about

in the data. Unless some prior information about

is provided the posterior distribution for

will tend to have a heavy upper tail (Gelman

2006).

The generalized ratio-of-uniforms method used by rust can

fail for heavy-tailed densities and this is indeed the case for these

data if we try to sample directly from

using the rust package’s default settings for the generalized

ratio-of-uniforms algorithm. One solution is to reparameterize to

,

which hanova1 implements by default. Another possibility is

to increase the generalized ratio-of-uniforms tuning parameter

r from the default value of 1/2 used in rust.

These approaches are illustrated below.

coag1 <- hanova1(resp = coagulation[, 1], fac = coagulation[, 2], n = 10000)

coag2 <- hanova1(resp = coagulation[, 1], fac = coagulation[, 2], n = 10000,

param = "original", r = 1)

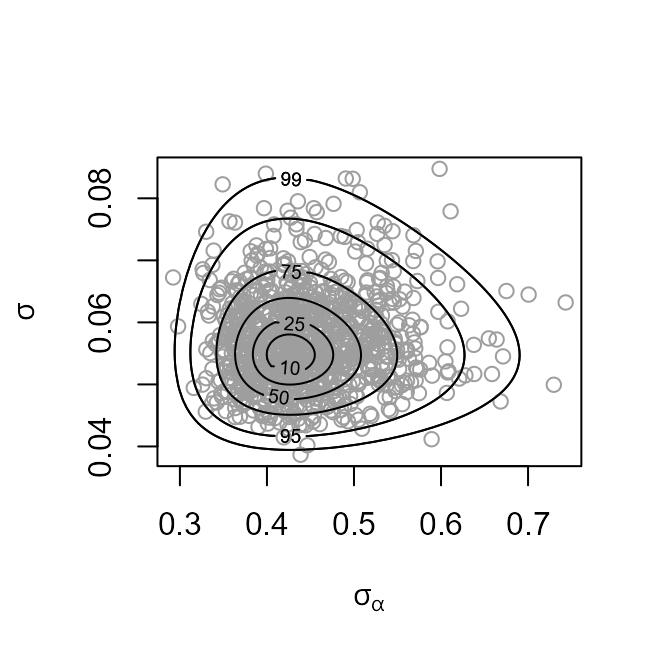

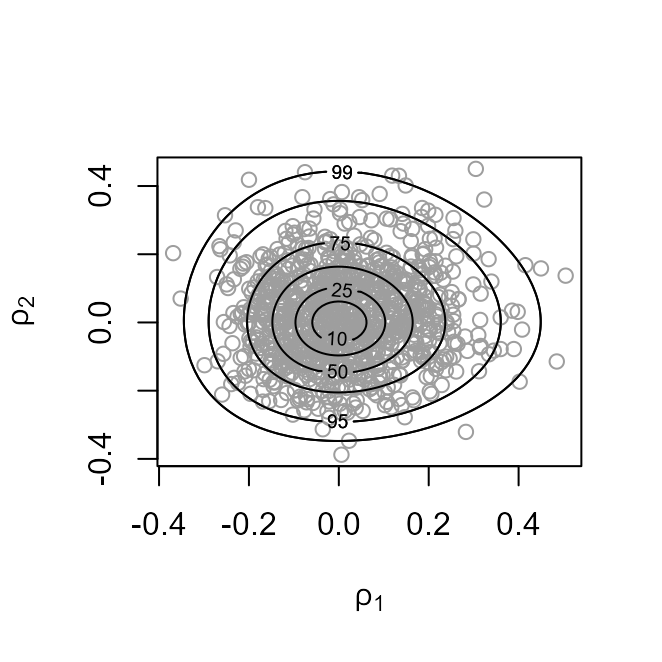

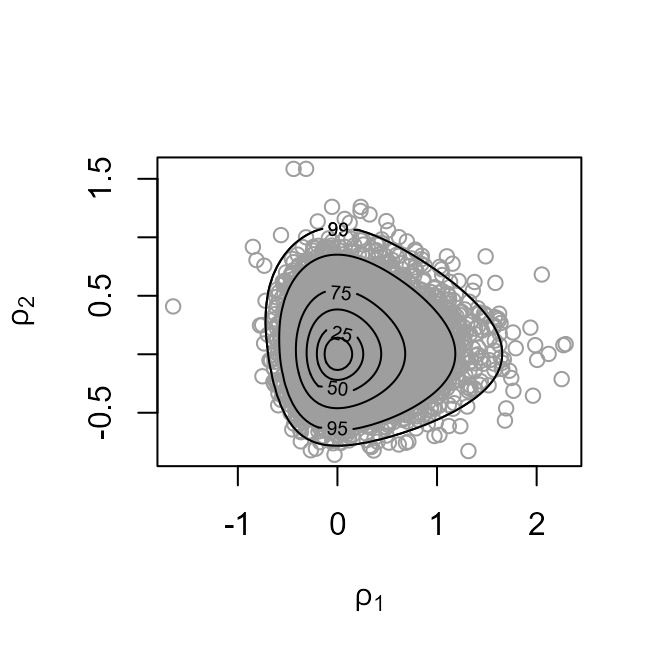

plot(coag1, params = "ru")

plot(coag1, ru_scale = TRUE)

The heaviness of the upper tail of the marginal posterior density of

is evident in the plot on the left. Parameter transformation to

results in a density (in the plot on the right) from which it is easier

to simulate.

We produce some summaries of the posterior sample stored in

coag1. The summaries calculated from coag2 are

very similar.

probs <- c(2.5, 25, 50, 75, 97.5) / 100

all1 <- cbind(coag1$theta_sim_vals, coag1$sim_vals)

round(t(apply(all1, 2, quantile, probs = probs)), 1)

#> 2.5% 25% 50% 75% 97.5%

#> theta[1] 58.8 60.4 61.2 62.0 63.8

#> theta[2] 64.0 65.2 65.9 66.5 67.9

#> theta[3] 65.7 67.1 67.8 68.4 69.8

#> theta[4] 59.4 60.5 61.1 61.7 62.9

#> mu 54.7 62.2 64.0 65.7 73.2

#> sigma[alpha] 2.0 3.5 5.0 7.9 27.0

#> sigma 1.8 2.2 2.4 2.7 3.4

These posterior summaries are similar to those presented in Table

11.3 of Gelman et al. (2014) (where

is denoted

),

which were obtained using Gibbs sampling.

When the number of groups is small Gelman

(2006) advocates the use of a half-Cauchy prior for

.

The code below implements this using independent half-Cauchy priors for

and

,

that is,

We choose, somewhat arbitrarily,

:

in practice

should be set by considering the problem in hand. See Gelman (2006) for details. We set

to be large enough to result in an effectively flat prior for

.

coag3 <- hanova1(resp = coagulation[, 1], fac = coagulation[, 2],

param = "original", prior = "cauchy", hpars = c(10, 1e6))

Appendix

Consider the hierarchical 1-way ANOVA model

where

and

and all random variables are independent. We specify a prior density

for

.

Let

and

.

Marginal posterior density of

The joint posterior density of

satisfies

where

.

Let

.

Completing the square in

in the term in square brackets gives

where

and

.

Therefore,

The marginal posterior density of

is given by

Manipulating

gives

Therefore, the joint

posterior density of

satisfies

where

,

and

.

A special case

Suppose that a

)

prior distribution is specified for

,

so that

and that

and

are independent a priori. We derive the marginal posterior

density for

in this case and the conditional posterior density of

given

.

The joint posterior density for

satisfies

Completing the square in

in

gives

where

.

Therefore,

Retaining only the terms in

that involve

gives

Therefore,

.

The conditional posterior density of

given

The conditional posterior density of

given

satisfies

because these are the only

terms in

that involve

.

Therefore, conditional on

,

are independent a posteriori and

,

where

Noting that

gives

,

where

Factorisations for simulation

In the most general case considered here the factorisation

means that we can simulate

first from the three-dimensional

and then, conditional on the value of

,

simulate independently from each of the normal distributions of

.

In the special case detailed above the factorisation becomes

Therefore, the first stage

can be performed by simulating from the two-dimensional

and then, conditional on the value of

,

from the normal distribution of

.

References

Gelman, A. 2006.

“Prior Distributions for Variance Parameters in

Hierarchical Models.” Bayesian Analysis 1

(3): 515–33.

https://doi.org/10.1214/06-BA117A.

Gelman, A., J. B. Carlin, H. S. Stern, D. B. Dunson, A. Vehtari, and D.

B. Rubin. 2014.

Bayesian Data Analysis. Third. Florida, USA:

Chapman & Hall / CRC.

http://www.stat.columbia.edu/~gelman/book/.

Northrop, P. J. 2017.

rust:

Ratio-of-Uniforms Simulation with Transformation.

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rust.

Northrop, P. J., and R. E. Chandler. 2014.

“Quantifying Sources of

Uncertainty in Projections of Future Climate” 27: 8793–8808.

https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00265.1.