Chapter 5: Random Variables

Paul Northrop

Source:vignettes/stat0002-ch5-random-variables-vignette.Rmd

stat0002-ch5-random-variables-vignette.RmdThis vignette provides some R code that is related to some of the content of Chapter 5 of the STAT0002 notes, namely to random variables and their properties.

Discrete random variables

We look at two example discrete random variables and consider how to find their respective modes, medians and means.

An example with finite support

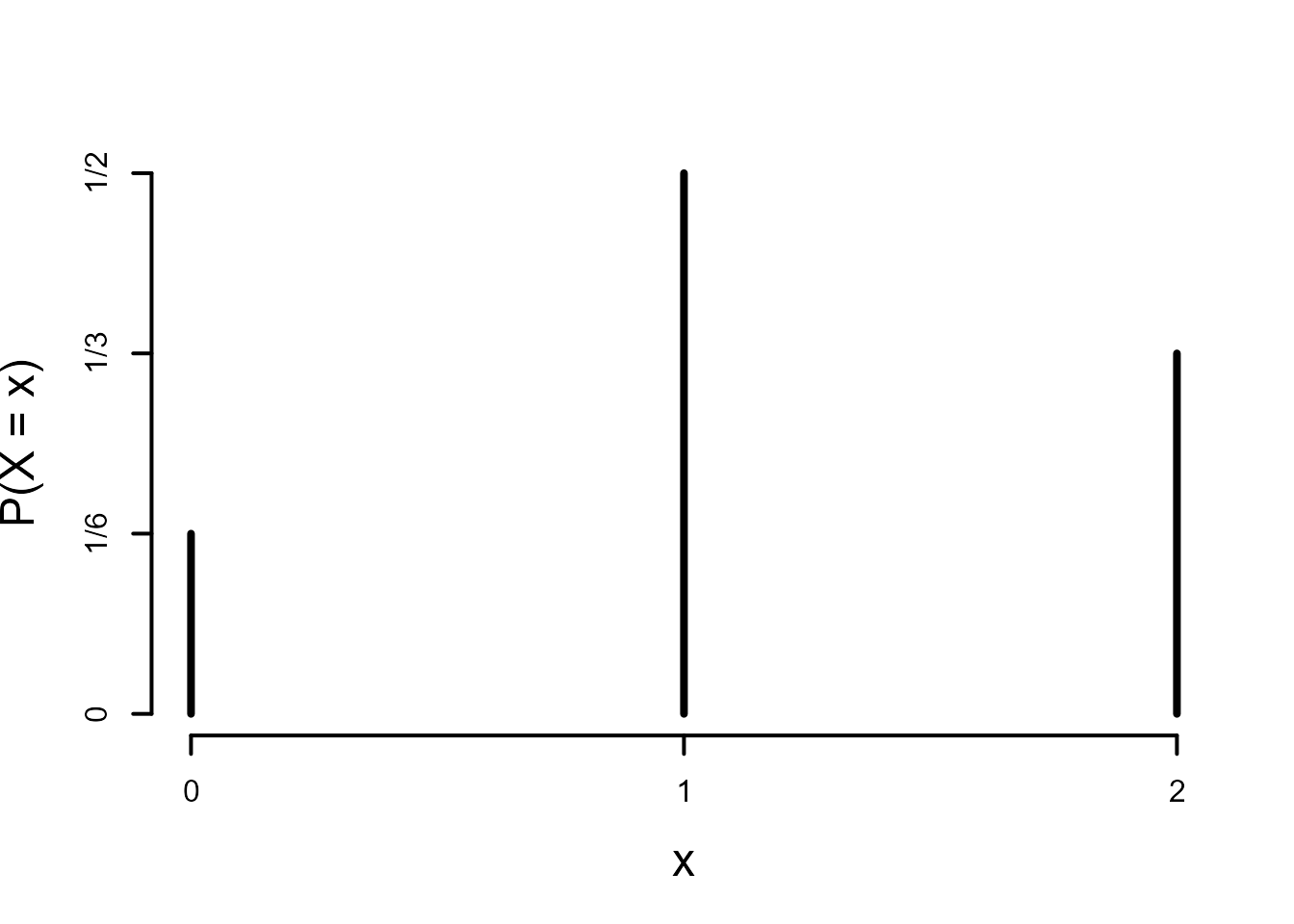

Consider the random variable \(X\) with support \(\{ 0, 1, 2 \}\) and p.m.f. satisfying

\[ P(X=0)=\frac16 \qquad P(X=1)=\frac12 \qquad P(X=2)=\frac13. \]

The following code produces plots of the p.m.f. and c.d.f. of \(X\), fiddling with the basic plots to produce a slightly prettier ones.

> # Plot the p.m.f.

> x <- 0:2

> px <- c(1/6, 1/2, 1/3)

> plot(x, px, type = "h", axes = FALSE, ylab = "P(X = x)", xlab = "x",

+ ylim = c(0, 1/2), lwd = 4, cex.lab = 1.5, cex.axis = 1.5, las = 1)

> axis(1, at = 0:2, lwd = 2)

> axis(2, at = c(0, sort(px)), labels = c("0", "1/6", "1/3", "1/2"), lwd = 2)

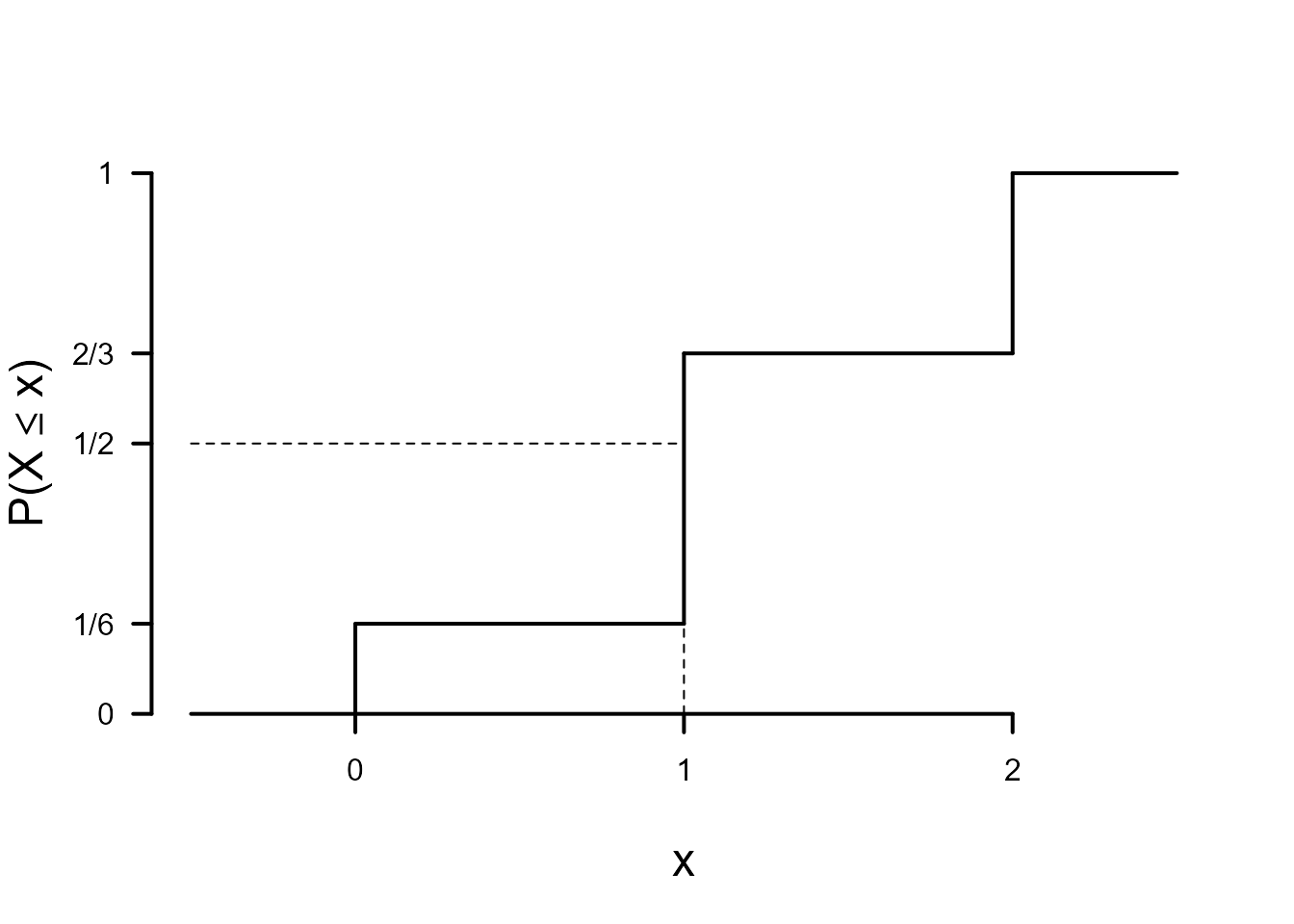

> # Plot c.d.f.

> x0 <- c(-0.5, 0, 0, 1, 1, 2, 2)

> y0 <- c(0, 0, 1/6, 1/6, 2/3, 2/3, 1)

> x1 <- c(0, 0, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2.5)

> y1 <- c(0, 1/6, 1/6, 2/3, 2/3, 1, 1)

> plot(c(x0, x1), c(y0, y1), axes = FALSE, ylab = "", xlab = "x", las = 1, type = "n", cex.lab = 1.5,

+ cex.axis = 1.5, lwd = 4)

> segments(x0, y0, x1, y1, lty = rep(1, 7), lwd = 2, pch = 0)

> axis(1, at = 0:2, labels = 0:2, pos = 0, lwd = 2)

> axis(2, at = cumsum(c(0, px)), labels = c("0", "1/6", "2/3", "1"), las = 1, lwd = 2)

> title(ylab = expression("P(X"<="x)"), cex.lab = 1.5, line = 2.5)

> # Add lines to indicate the median of X

> axis(2, at = 1 / 2, labels = "1/2", las = 1, lwd = 2)

> segments(-0.5, 1 / 2, 1, 1 / 2, lty = 2)

> segments(1, 0, 1, 1 / 2, lty = 2)

The plot of the p.m.f. shows that the mode of \(X\) is 1 and the plot of the c.d.f. that the median of \(X\) is 1. This random variable has finite support. Therefore, its mean \(\text{E}(X)\) exists. We could calculate \(\text{E}(X)\) using the following code.

An example with infinite support

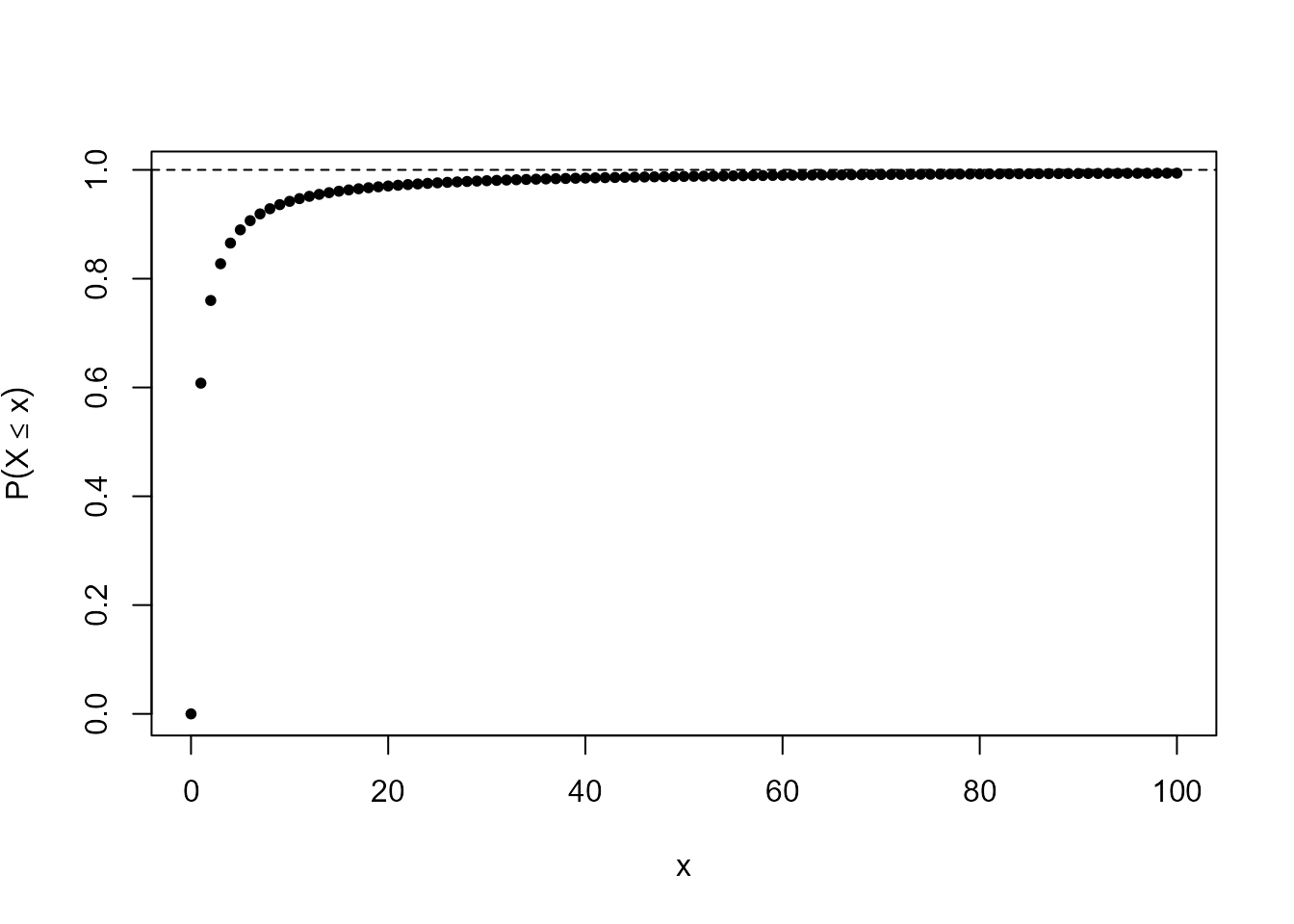

Consider the function \[ p(x) = P(X = x) = \frac{6}{\pi^2} \frac{1}{x^2}, \quad \mbox{ for } x = 1, 2, 3,\, ....\]

This is a valid p.m.f. of a discrete random variable \(X\), because

- \(p(x) \geq 0\) for \(x = 1, 2, 3,\, ...\)

- \(\sum_{x=1}^{\infty} p(x) = 1\) (Basel problem)

To illustrate 2. look at the following output and plot.

> m <- 100

> x <- 1:m

> px <- (6 / pi ^ 2) / x ^ 2

> mat <- cbind(c(0, x), cumsum(c(0, px)))

> plot(mat[, 1], mat[, 2], pch = 20, ann = FALSE)

> title(xlab = "x", ylab = expression(P(X <= x)))

> abline(h = 1, lty = 2)

> tail(mat)

[,1] [,2]

[96,] 95 0.9936343

[97,] 96 0.9937003

[98,] 97 0.9937649

[99,] 98 0.9938282

[100,] 99 0.9938902

[101,] 100 0.9939510Can you find the median, mode and mean of \(X\)?

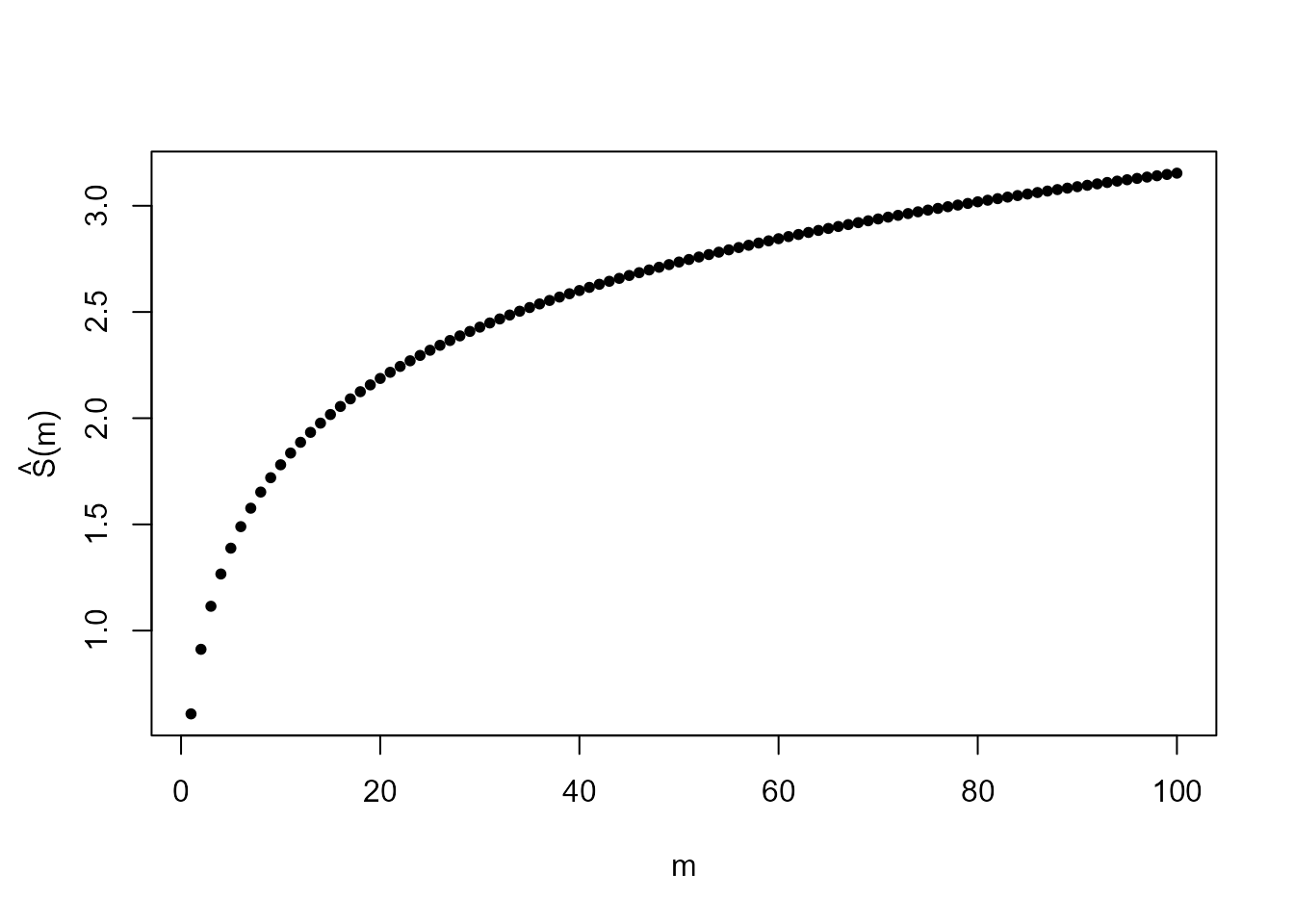

You will have trouble finding the mean because \(S = \sum_{x=1}^{\infty} x p(x)\) does not converge. Suppose that we try to approximate the value of this sum using \(\hat{S}(m) = \sum_{x=1}^{m} x p(x)\) for some large value \(m\). The following code plots the \(\hat{S}(m)\) against \(m\) for \(m = 1,..., 100\).

> m <- 100

> x <- 1:m

> px <- (6 / pi ^ 2) / x ^ 2

> s <- cumsum(x * px)

> plot(x, s, pch = 20, ann = FALSE)

> title(xlab = "m")

> title(ylab = expression(hat(S)(m)), line = 2.25)

Does it look like \(\hat{S}(m)\) is converging as \(m \rightarrow \infty\)? You could try some larger values of \(m\) to investigate. You could also examine \(\sum_{x=1}^{\infty} x p(x)\) algebraically. Does it involve an example series that you have seen before? Is this series convergent or divergent?

This distribution is a special case of a Zeta distribution, where a

parameter \(s= 2\). This distribution

has a (finite) mean only if \(s >

2\). If \(s \in (1, 2]\) then we

can argue either that this distribution has no mean or that it has an

infinite mean. If we simulate samples of finite size from a Zeta

distribution with \(s = 2\) then we can

calculate the sample means of these samples. However, these sample means

are of little use to us because this distribution does not have a finite

mean. The values of these sample means are liable to be influenced by

the values of the largest sample values which may be very large. The

VGAM R package has a function rzeta that

simulates samples from a Zeta distribution. If you would like to explore

how these sample means behave then you can use the code below. You could

repeat this a few times and look at how the sample means vary. When

using the VGAM package setting the argument

shape = 1 corresponds to the distribution that we have

considered.

Continuous random variables

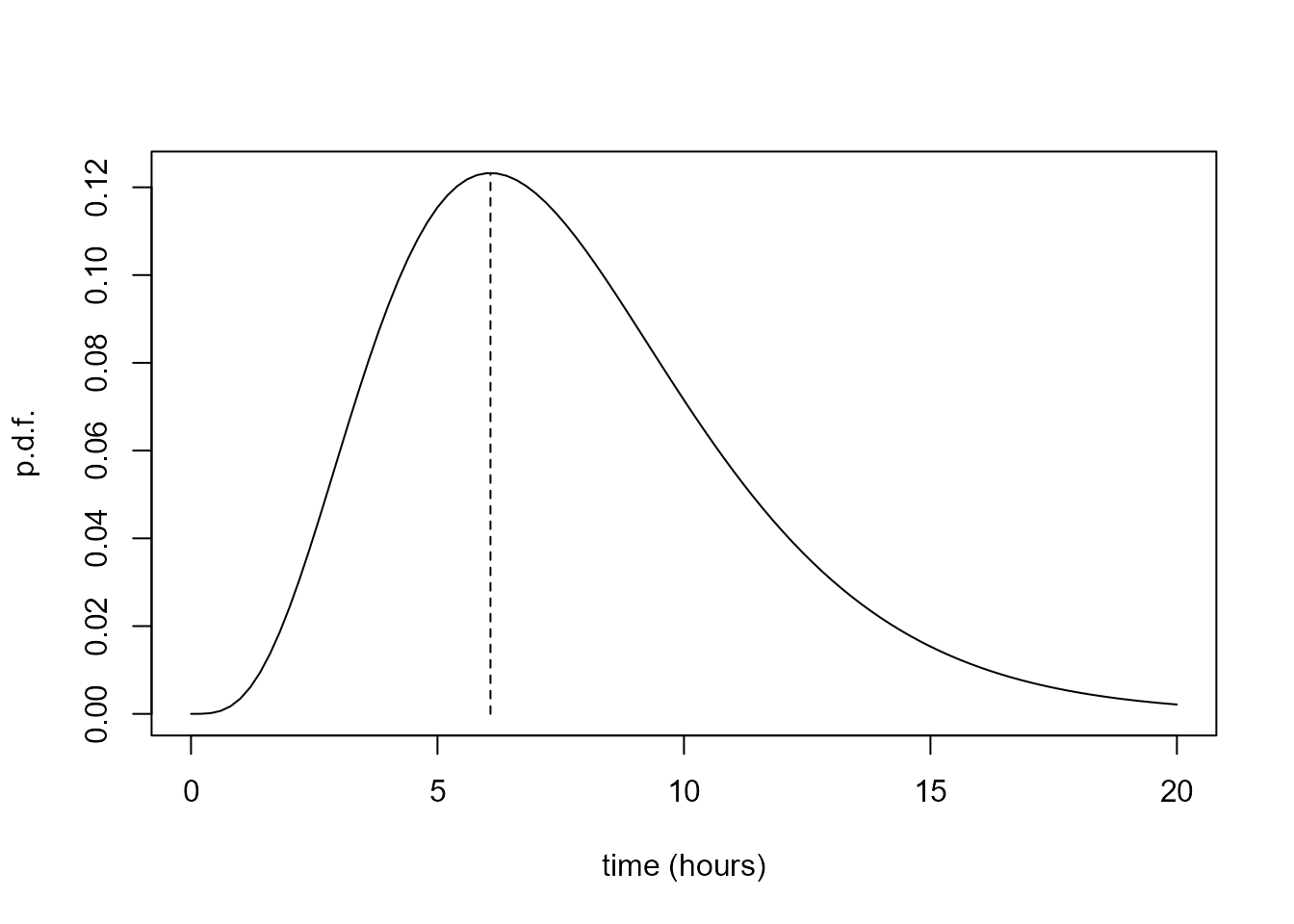

We look at a continuous random variable that may be used to model the Oxford birth times data and consider how to calculate the mode, median and mean of this random variable.

A simple model for the Oxford birth times

The plot in the bottom of Figure

5.2 of the notes is of the p.d.f. of a gamma distribution with

parameters chosen so that the shape of the p.d.f. is similar to that of

the histogram of the times in the Oxford Birth Times dataset. To find

out about the gamma distribution type ?GammaDist. The

following code finds values of the shape parameter \(\alpha\) and scale parameter \(\sigma\) for which the mean and variance of

the gamma distribution are equal, respectively, to the sample mean and

sample variance of the Oxford birth times data.

Can you see how this works?

> library(stat0002)

> tbar <- mean(ox_births$time)

> vart <- var(ox_births$time)

> # Sample mean and variance

> c(tbar, vart)

[1] 7.723158 12.731320

> scale_par <- vart / tbar

> shape_par <- tbar / scale_par

> # Estimates of gamma shape and scale parameters

> c(shape_par, scale_par)

[1] 4.685073 1.648460We produce a basic plot of the gamma distribution that we have fitted to these data, to check that it has done what we expected. If \(\alpha\) is greater than 1 then the mode of a gamma(\(\alpha, \sigma\)) distribution is at \((\alpha - 1) \sigma\). We add a vertical line at the mode to check this.

> # Produce the plot

> curve(dgamma(x, shape = shape_par, scale = scale_par), 0, 20, ylab = "p.d.f.", xlab = "time (hours)")

> gmode <- (shape_par - 1) * scale_par

> gmode

[1] 6.074698

> # Indicate the mode

> segments(gmode, 0, gmode, dgamma(gmode, shape = shape_par, scale = scale_par), lty =2)

A digression about numerical optimisation

If we did not know how to find the mode using the values of \(\alpha\) and \(\sigma\) then we could try to find it

numerically by searching for the point at which the p.d.f. is maximised.

For functions like this it is common to seek to maximise the

log of the p.d.f.. In practice, optimisation

algorithms, like the function optim used below, are often

set up to minimise a function by default. Here we set

the control option fnscale to -1 to multiply

the target function by \(-1\), turning

our maximisation problem into a minimisation problem.

Note the use of ... to pass the values of

shape, scale and log to the

function fn. Also, method = "L-BFGS-B" chooses

an optimisation method that allows us to set bounds on the solution and

lower = 0 gives the information that we know that the mode

cannot be less than zero.

> # A function to calculate the (log of the) gamma p.d.f.

> fn <- function(x, ...) dgamma(x, ...)

> find_mode <- optim(1, fn, shape = shape_par, scale = scale_par, log = TRUE,

+ method = "L-BFGS-B", lower = 0, control = list(fnscale = -1))

> # Approximate value of the mode

> find_mode$par

[1] 6.074697

> # Value of the p.d.f. at this value

> exp(find_mode$value)

[1] 0.1232569A digression about numerical integration

It can be shown algebraically that the gamma p.d.f. integrates to 1.

(This must be true otherwise it is not a p.d.f..) R has a function

called integrate that performs numerical integration to

estimate the value of an integral. The code below uses

integrate to check that this gamma p.d.f. integrates to 1

over \((0, \infty)\).

> # Check that the p.d.f. integrates to 1

> integrate(dgamma, 0, Inf, shape = shape_par, scale = scale_par)

1 with absolute error < 1.1e-08We could also use integrate to check that our fitted

gamma distribution has the mean that we expect. Note that the

... in the definition of the function

integrand that calculates the integrand can be used to pass

the arguments shape and/or scale to the

function dgamma that calculates the p.d.f. of a gamma

distribution.

> # Check that the gamma mean is equal to the sample mean, tbar, of the data

> integrand <- function(x, ...) x * dgamma(x, ...)

> integrate(integrand, 0, Inf, shape = shape_par, scale = scale_par)

7.723158 with absolute error < 3e-07

> tbar

[1] 7.723158The qgamma function can be used to calculate quantiles

of a given gamma distribution. Suppose that we wish to calculate the

median (the \(50\%\) quantile) of our

fitted gamma distribution. The following code does this. It also shows

that we can calculate more than one quantile at a time.

> tmedian <- qgamma(1 / 2, shape = shape_par, scale = scale_par)

> tmedian

[1] 7.181169

> qgamma(c(0.05, 0.5, 0.95), shape = shape_par, scale = scale_par)

[1] 2.926326 7.181169 14.370700We could use integrate to check that qgamma

has returned the correct median, or use the function

pgamma, which calculates the c.d.f. of a gamma random

variable.